10 things you never knew about funeral home history? Yes. Burial ceremonies have existed since the beginning of time but many traditions have changed. Our ancestors’ experiences when someone died were quite different from our own.

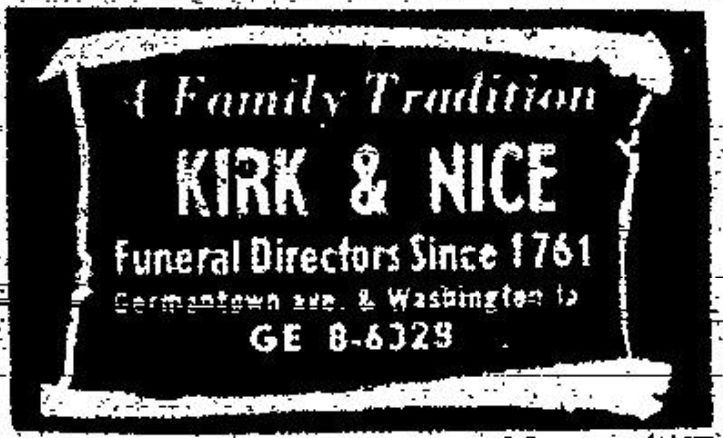

The first funeral home in the United States was Kirk and Nice, founded in 1761. It was a family-owned business.

The number of funeral homes continued to grow into the 1900s. With the growth, it became important to have formal training for undertakers for consumer protection and industry standardization. So in 1882, the National Funeral Directors Association was established at a convention in Rochester, New York. Membership in the organization helped clients determine if the funeral directors were professionals.

Cemetery managers, coffin builders, florists, life insurance agencies, and others in related fields followed suit, causing the funeral home business to grow even more. By 1920, there were about nearly 25,000 funeral homes in the United States, a 100% growth in less than 80 years.

Here are 10 things you never knew about funeral home history.

#1 Things you never knew about funeral home history

Embalming

Funeral homes might seem like they’ve been around forever, but they really didn’t emerge in the United States until the mid-1800s.

The US Civil War

The main shift in funeral history occurred around 1860 – 1865 during the American Civil War. The Civil War brought more deaths to America than any other war before or since. Funeral traditions had to be adapted to accommodate the large numbers of dead in such a short period.

| War (and years of U.S. military involvement) | Number of fatalities |

|---|---|

| American Civil War (1861-1865) | 620,000 |

| World War II (1939-1945) | 405,399 |

| World War I (1917-1918) | 116,516 |

| Vietnam War (1965-1973) | 58,209 |

One of the biggest problems was getting the deceased from the battlefield to their homes before decay set in. Bodies were sent home on trains packed in ice but most had to be buried close to the battlefields, far from home.

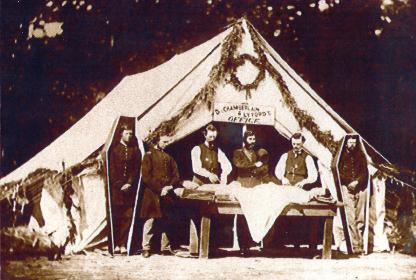

Some began to think of the process of embalming. Embalming originated thousands of years ago in Egypt but it was used for the first time in the United States during the Civil War.

President Abraham Lincoln took a great interest in the process of embalming. He studied the work being done by Dr. Auguste Renouard, which became the foundation for today’s methods of embalming.

The formaldehyde used in embalming was discovered in 1859 by Russian chemist Aleksandr Butlerov. It allowed bodies to be shipped and gave families who lived at a distance time to gather.

Dr. Benjamin F. Lyford and Dr. C.B. Chamberlain at their “embalming tent” at Camp Letterman in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; November 1863.

President Lincoln directed the Quartermaster Corps to utilize embalming to ensure that Union soldiers who had died while enlisted could be returned to their hometowns for burial.

The captain of the Army Medical Corps in Washington, D.C., Dr. Thomas Holmes, embalmed more than 4,000 soldiers and officers. When Thomas realized the commercial potential of embalming, he resigned his military commission and began offering the procedure to the public for $100.

In 1865, embalming gained popularity very quickly when President Lincoln was embalmed following his assassination.

Lincoln was the first public figure to be embalmed and his body was transported by train throughout much of the nation for nearly three weeks. Stops included the cities of Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Chicago.

#2 Things you never knew about funeral home history

From the “Funeral Parlor” to the “Living Room”

Before the mid-1800s, it was considered disrespectful to have a funeral at a funeral parlor. This was only done when someone didn’t have family or friends to take care of the services at home.

The parlor was the room where visiting guests were received but most of the time it sat vacant and unused.

The doors on the parlor were usually kept closed during everyday life. The fireplace sat cold and empty. The furniture was covered with large cloths to keep the dust off and to keep the sun from fading the fabric.

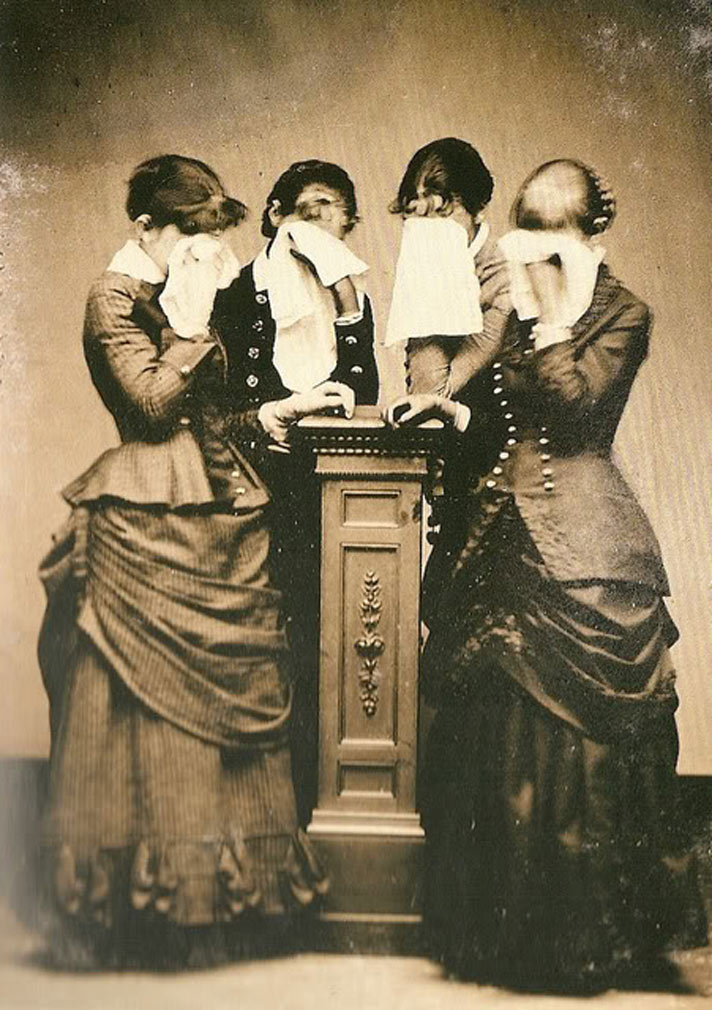

But when the family was preparing the Victorian home for a funeral, the parlor became a beehive of activity. In fact, it required a total transformation of the front parlor.

Most people died close to their homes and their bodies were displayed in the family’s parlor for several days before burial. The bodies were often placed on ice and surrounded by fragrant flowers.

But following President Lincoln’s funeral, people began to think of embalming as not only acceptable but preferred. If it was good enough for Lincoln, it was good enough for their family.

Embalming allowed bodies to be transported from the home to more public settings where more people could be invited to the funeral services. Funerals were gradually shifted from the home parlor to the business-run “funeral parlor”. Many are still called that today.

This transition of the funeral from the home to the funeral director’s place of business also led to the death of the formal “parlor” in many American homes. In 1910, the Ladies’ Home Journal renamed the “parlor” the “living room”, returning it to the family for their enjoyment.

Modern funeral homes practice many of the same traditions that were widely used when preparing the Victorian home for a funeral, such as hanging black wreaths, tying crepe swags, setting up coffin stands, and displaying mementos of the deceased.

Learn more about Victorian cemetery traditions by clicking HERE.

#3 Things you never knew about funeral home history

From Undertakers to Morticians to Funeral Directors

In 1882, the Clarke School in Cinncinnati, Ohio became the first mortuary school in the United States. Clarke is known as the “father of American embalming schools”, where undertakers recieved formal training and embalming practices were standardized. Today, the Clarke School offers associate and bachelor’s degrees in mortuary science.

In 1894, Virginia became the first state to pass embalming laws. By 1900, 24 states had enacted similar laws. Funeral directors were encouraged by the new National Funeral Directors Association to consider their line of work as a profession rather than just a trade.

Along with the change in practices, came a change in title. Early in the 1900s, the title of “undertaker” was changed to “mortician”, and then in the following years, to “funeral director”.

#4 Things you never knew about funeral home history

The Undertaker’s Ads

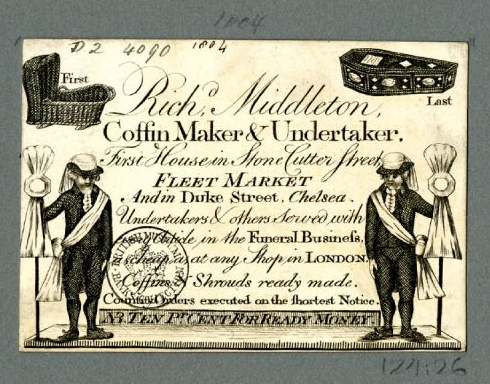

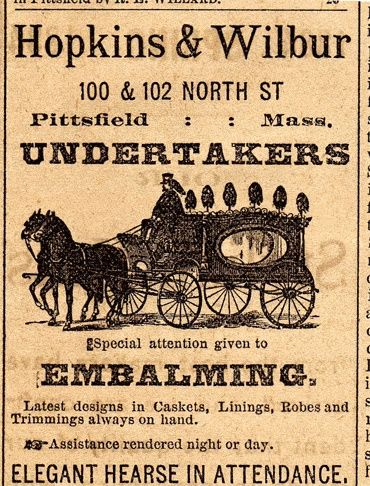

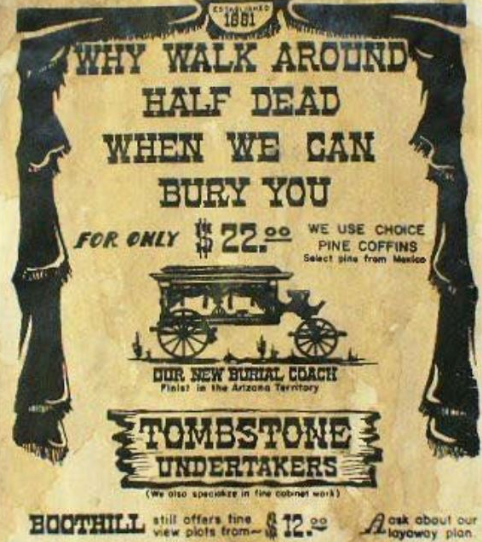

Undertaker’s ads give us a peek into early funeral home history.

From the cradle to the coffin, this London undertaker provided a place to rest. You could even get a 10% discount for paying cash.

This Massachusetts undertaker offers a fancy horse-drawn hearse decorated with ostrich plumes, a driver with a top hat, and the latest designs in caskets – as well as embalming.

Just in case you haven’t bought into the whole idea yet, here’s a tempting ad: “Why walk around half-dead when we can bury you for only $22?” Indeed!!

Who would want to miss out on this fine deal from the 1880s . . . choice pine coffins and the finest burial coach in the Arizona Territory”?

Boothill Cemetery was offering plots for just $12 and up. And if that didn’t get you, the ad encourages you to ask about their layaway plan. (“Layaway”, get it? Nah, I’m sure there was no pun intended.) I bet you could even be buried with your boots on!

#5 Things you never knew about funeral home history

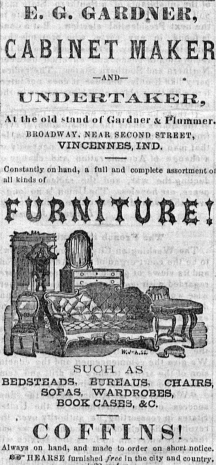

From Cabinet Maker to Undertaker

Furniture-maker turned undertaker . . . it almost sounds like a line from a nursery rhyme, doesn’t it?

Most undertakers in the 1800s were carpenters first. So it was only logical that townsfolks would turn to someone who already had wood, tools, and know-how to build their coffins.

From there, it was just a natural extension to have the coffin-maker conduct the funeral. And drive the hearse. And provide the music for the services. And serve the family meal. And dig the grave. And turn their home into a boarding house for out-of-town guests who came in for the funeral. The undertaker was a true servant to his community.

“And, oh yes,” the customers asked, “could you still build us a table and chair set for our dining room?” Whew! Undertakers were masters of many trades all rolled into one!

In 1837, the Cleveland City Directory in Ohio listed 13 area cabinetmakers. All were “available on short notice,” a polite phrase meaning that they made coffins.

Twenty years later, the 1857 Cleveland City Directory listed 16 cabinetmakers, now called furniture makers. Ten of them were also now listed as undertakers.

From their addresses, we can see that most were side-by-side or front-and-back or up-and-down shops. Furniture was sold in one half of the store while the other half served as the undertaking business.

Ready-made coffins were available, from ordinary pine boxes with nail-on lids for about $5 to mahogany coffins for $50. The more expensive coffins had spring-release lids that could be opened from the inside or glass windows, just in case the “deceased” was not actually “deceased” but in a coma.

The early undertaker’s establishment did not usually include a funeral parlor since funerals were still held in private homes.

The Undertaker and his Wife

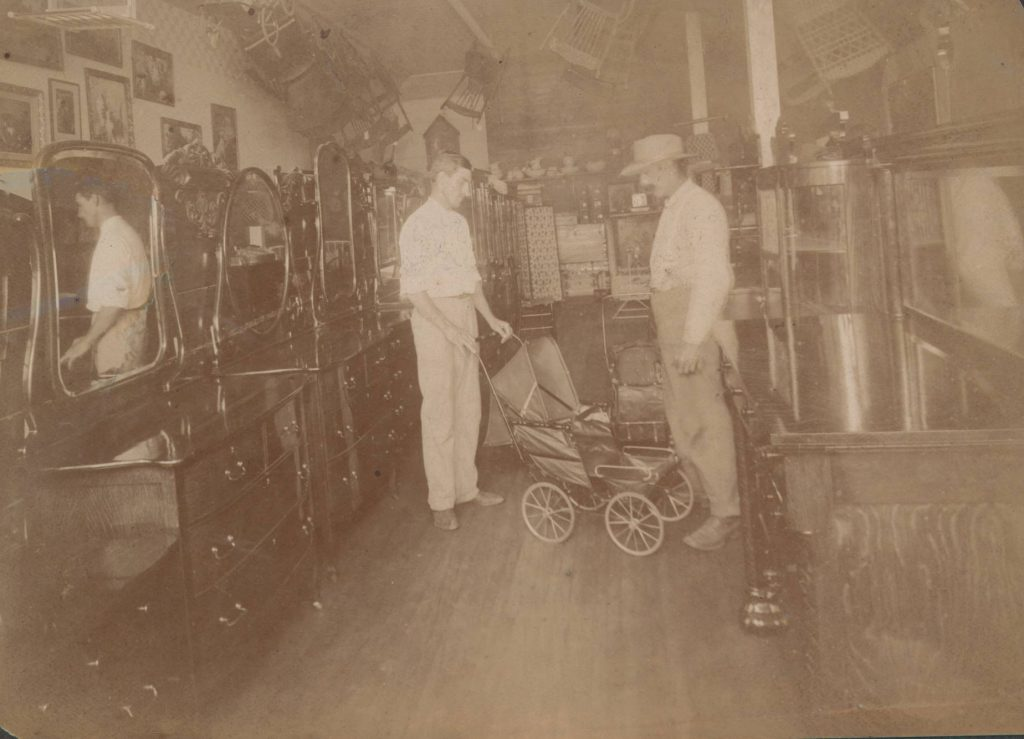

The photo above is of my great-grandfather, George Gilbert. Like many of his day, he first made furniture and then he became an undertaker.

In fact, two of my great-grandfathers were undertakers in the 1800s. They met one another through the undertaking business as young men. Then they each married wives and had children. The daughter of one grew up to marry the son of the other . . . and those were my grandparents.

As business increased in George Gilbert’s furniture store, he ordered furniture from others to resell. He sold dressers and sideboards, sewing machines and pianos, rocking chairs and baby buggies. In the photo above, George is on the left giving a sales pitch to the customer in the hat.

Horse-drawn Hearse

Embalming created a need for transportation from homes or hospitals, so hearses and ambulances became a common part of the funeral business. My great-grandfather George Gilbert built a wooden horse-drawn buggy hearse with curtained windows.

Many undertakers in the late 1800s and early 1900s had hearses for rent.

Since funeral directors often lived on-site, they commonly employed family members to perform duties. Family-operated funeral homes continue to be typical in many communities.

George Gilbert’s wife, Nina, sang hymns at the town funerals. She served pies and stews. She let travelers spend the night in their guest bedrooms. Gradually, their home became a “bed and breakfast” boarding house for travelers who came to mourn for those who had passed on.

#6 Things you never knew about funeral home history

Funerals For Rent

The undertakers rented chairs for the family’s parlor. They rented mourning clothes from top hats to dresses to gloves. For the home decor, they had memorial books, black wreaths, and black crepe swags.

After embalming schools opened throughout the United States, most new undertakers entered the profession through embalming practices rather than furniture making. When funerals were still held in private homes, undertakers brought embalming equipment to the home to prepare the body of the deceased – often right in their own beds.

If the distance between the home and the cemetery was not too far, the coffin was carried by family members and the undertaker’s staff. For more lavish funerals, the undertaker rented horse-drawn carriages to transport the body to the cemetery.

Funeral home history reveals that the undertaker had many items for rent. When a loved one died, family members could rent some of the following items from the undertaker so they could conduct the funeral on their own or with the help of the undertaker.

Wreath

Most wreaths in our day are hung to celebrate Christmas. But it was not always so.

One of the most common Victorian funeral traditions was to hang a wreath on the front door when a family member died.

The wreath let community members know that there had been a death in the household so that they could pass by quietly out of respect. Even children were taught to play on a different street out of ear-shot of a home with a wreath on the door.

Most funeral wreaths were made up of black ribbons or black crepe.

The most expensive wreaths were made of black ostrich feathers.

Podiums and columns

Undertakers rented podiums for speakers giving eulogies and wooden columns for family photos.

Velvet Backdrop

A portable velvet drapery was set up in the corner of the room or against a wall. It would become the backdrop for the coffin.

Coffin Stands

Coffin-stands were set up in front of the back-drop. Some had wheels to make it easy for pall-bearers to move the heavy coffins. Other coffin stands were made of wood.

#7 Things you never knew about funeral home history

Organs

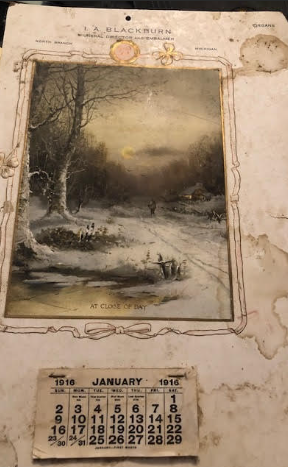

Someone wrote to me recently to ask, “Why would a calendar handed out by a funeral home dated 1916 have the word ORGANS printed at the top right-hand corner if organs were in fact not removed at that time in history? Do you have any idea what they meant by organs?”

My first thought is that the funeral home had organs – musical instruments – that could be used during funeral services, similar to a piano.

I called Blackburn Funeral Home in North Branch to see if they knew what the word “organs” meant on the 1916 calendar. They said that there was no such thing as organ donations at that time and confirmed that the word referred to the fact that the funeral home had a musical instrument called an “organs”.

They also said that the funeral home may have had more than one organ but it could have been just one. It was called an “organs”.

The instrument was similar to today’s organ, but it was not uncommon at that time to call it an “organs” (plural), especially if it was a pipe organ. Each of the pipes was considered an “organ” therefore the entire unit was called an “organs”.

They also told me that in 1916, the Blackburn Funeral Home was located above the Blackburn Furniture Store. The building is now the Masonic Lodge. The furniture store sold just furniture initially, but then started renting out things like hearses and casket stands. Then the company transitioned into the funeral business.

Pipe organs were built for hospitals, hotels, yachts, fraternity lodges, town halls, high school auditoriums, colleges and universities, churches, private residences, Veterans’ homes, theaters, and funeral homes.

In the United States alone, tens of thousands of organs were built in a span of about 200 years, but only about 600 of them were specifically designed for funeral homes. The mortuary organs were low-cost pipe organs requiring little space and their tone was meant to meet the “emotional needs of the bereaved”.

#8 Things you never knew about funeral home history

Calling Cards

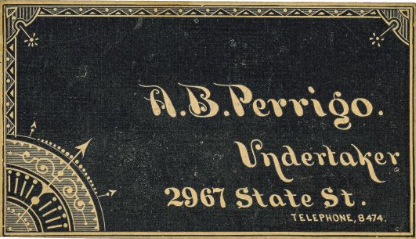

Undertakers and funeral homes had calling cards, similar to today’s business cards.

Many were black, in keeping with the somber nature of funerals.

Others were in full-color with cheerful illustrations.

#9 Things you never knew about funeral home history

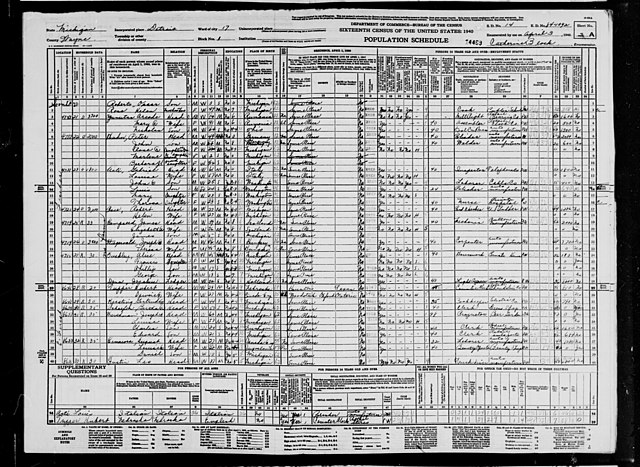

Undertaking was a Popular Occupation

According to the 1890 Census, nearly 10,000 people reported having the occupation of “undertaker”. In the 1900 Census, that number rose to roughly 16,000. Family-owned funeral homes became the norm in the early 1900s.

In 1918, the U.S. government prohibited public gatherings, including funerals and wakes because of the Spanish Flu pandemic. Flu victims had to be buried within 24 hours of death to prevent the spread of disease. Rather than a public event, funerals returned to being private affairs, confined to close family members.

#10 Things you never knew about funeral home history

A Genealogist’s Treasure

Tens of thousands of funerals have taken place in each of the millions of funeral homes around the world. Each one has a records of transactions, services rendered, burial locations, and family names. Funeral home business ledgers can be a genealogist’s treasure. They are often large, heavy books filled with pages that prove family residence locations and death dates.

In August 2006, Kirk and Nice Funeral Home, the first U.S. funeral home, acted to preserve their history with the help of the Genealogical Society of Utah, the Germantown Historical Society, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, where the original records are permanently stored. Many other funeral homes have acted to preserve their records as well.

Even funeral programs can be a great source of information. They sometimes detailed biographical information about the deceased, names of family members, birth and death dates, locations, church affiliations, the name of the cemetery where the burial took place, military service, and other personal details that may not be readily available elsewhere. Even a list pall-bearers, may give clues about those who may be family members of the deceased,

So if you are looking for family history information, don’t forget to check the funeral homes in the areas where your ancestors lived.

Volunteering to Take Gravestone Photos

The BillionGraves app helps preserve family memories. We need your help to take photos of gravestones! It is easy and done completely with your smartphone! Click HERE to get started.

Are you planning a group service project? Contact us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com for more resources. We’ll even help you find a cemetery that still needs to have photos taken.

You are welcome to do this at your own convenience, no permission from us is needed. If you still have questions after you have clicked on the link to get started, you can email us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com. We’ll be happy to help you!

Happy Cemetery Hopping!

Cathy Wallace